How do new species form on islands?

Much of my dissertation work focused on reconstructing the speciation process in birds that live in Oceania, inhabiting complex, fragmented island chains. Because open ocean typically serves as a barrier to dispersal in terrestrial vertebrate taxa (like birds), these island archipelagoes can generate lots of isolated populations, leading to explosive diversification. This natural experimental framework makes this an ideal region for studying the speciation process. Here I detail a few of the case studies that I’ve performed and highlight the meaningful advances my work has generated in our understanding of how evolution works in island systems.

Shedding new light on the “paradox of the great speciators”

- open access link to the manuscript: Genomic patterns in the dwarf kingfishers of northern Melanesia reveal a mechanistic framework explaining the paradox of the great speciators.

The “paradox of the great speciators” is a longstanding paradox, that asks how great speciator taxa can simultaneously be so good at dispersing that they reach dozens of islands, but so poor at dispersing that the population on each island becomes isolated and genetically differentiated? Multiple hypotheses have been suggested to explain the phenomenon, and we used the dwarf kingfishers (genus Ceyx) to test them.

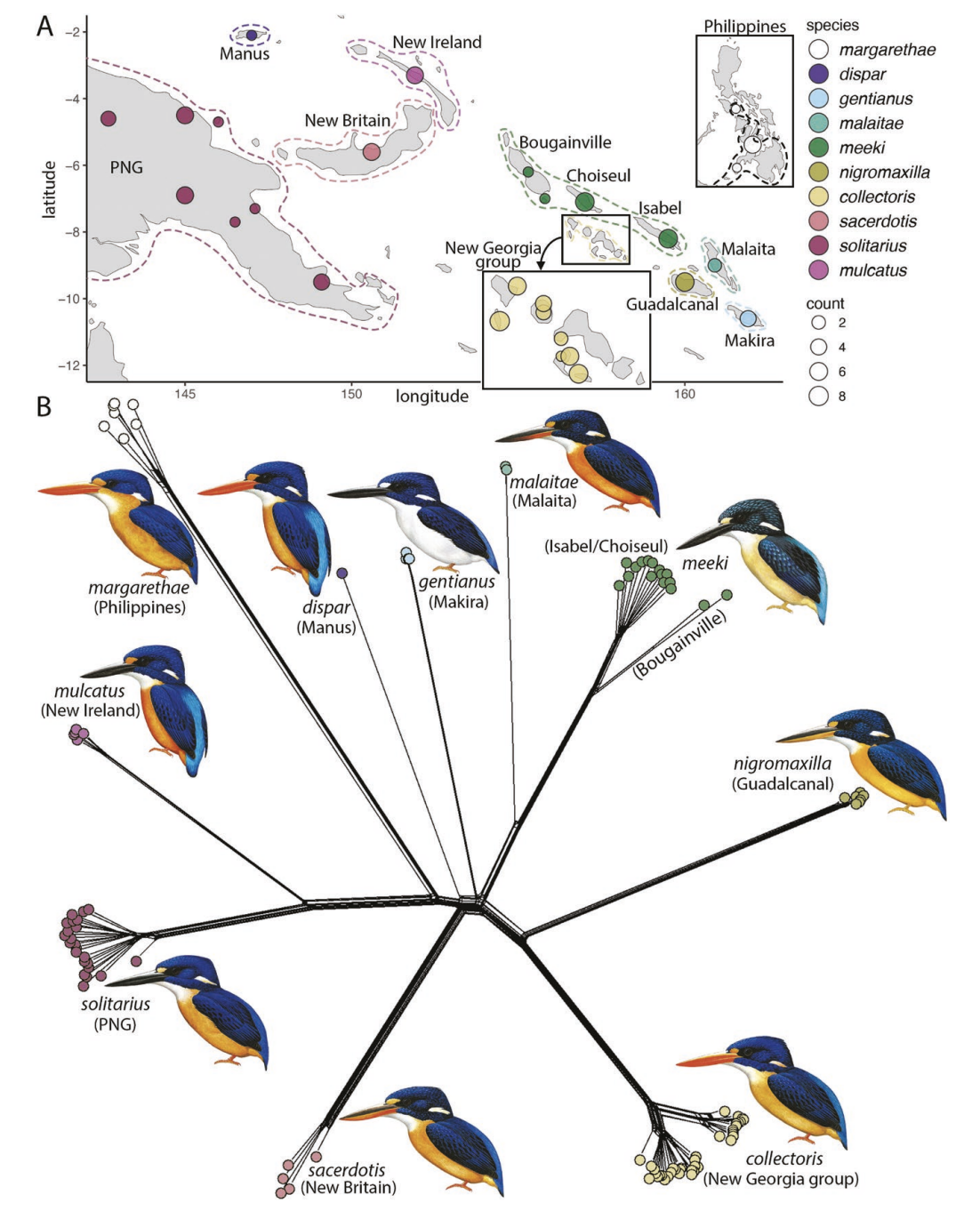

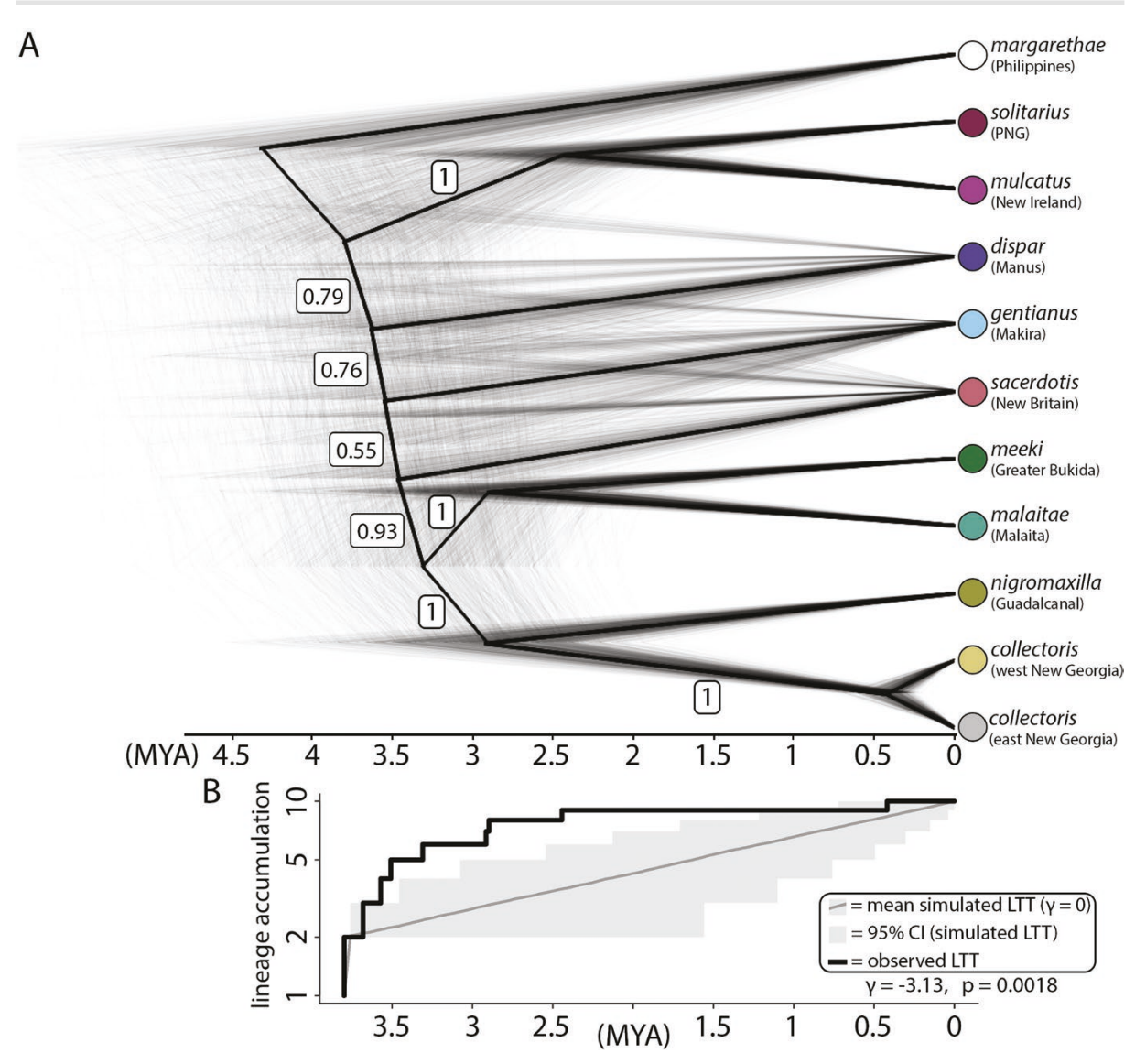

We see from this phylogenetic network that each island species is highly divergent and isolated, with no evidence for shared ancestry between the clades. To test for the tempo of diversification, we also constructed a time-calibrated phylogeny:

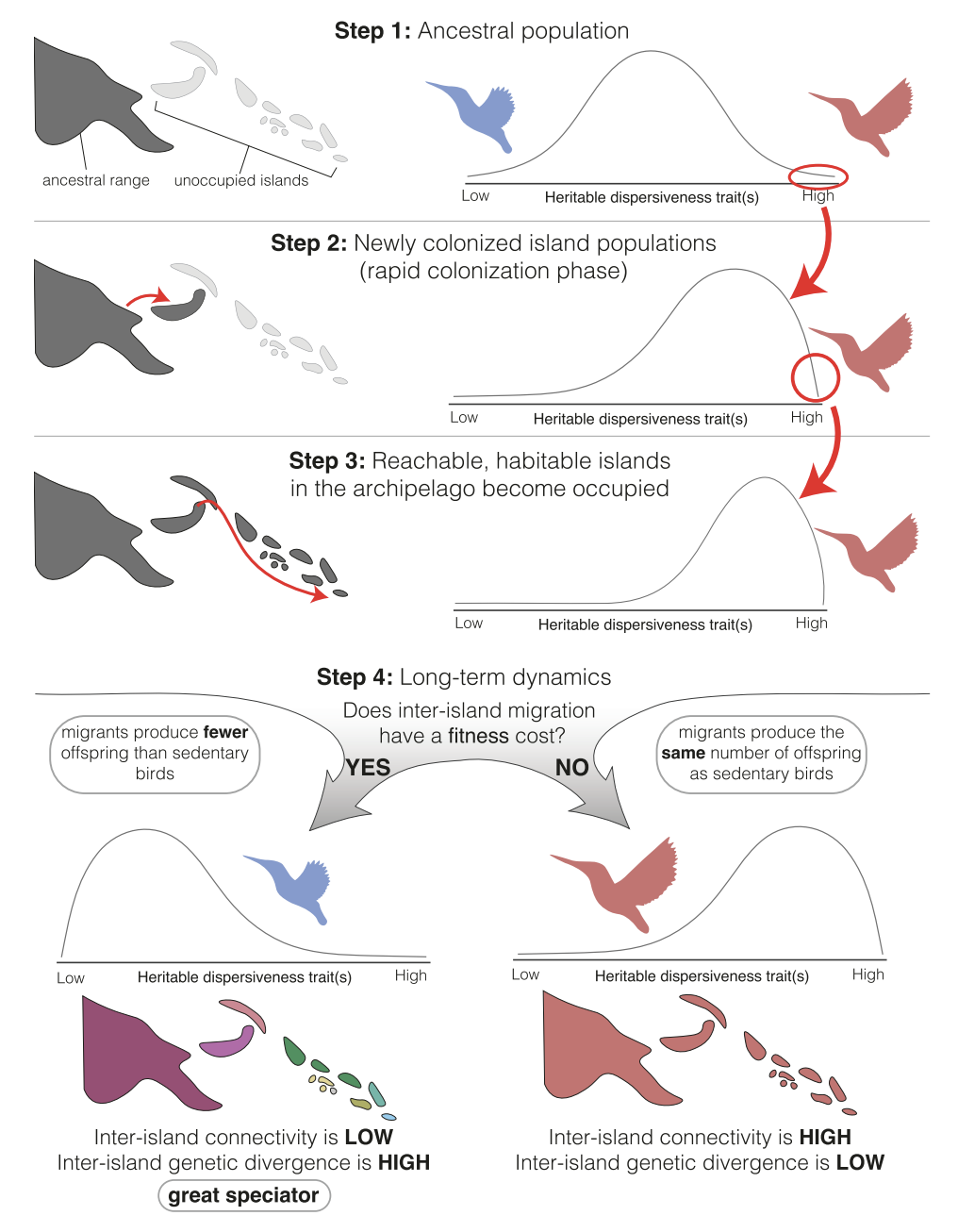

This reveals that there was a statistically significant early burst of diversification following the arrival of the ancestral Ceyx lineage in northern Melanesia. Based on this evidence, we were able to construct a fully fleshed out framework for how the “paradox of the great speciators” likely arises in island archipelagoes:

This diagram outlines how shifts in selection pressure on the “dispersiveness” trait throughout the colonization process can generate the exact paradoxical patterns that have been repeatedly documented in the ‘great speciator’ taxa of Oceania.

This project uses genomic data from specimens housed in natural history museums to document patterns of biodiversity, work that has formed the bread and butter of my research program. But I am particularly proud of this example, because it shows that with careful inference, these patterns can be used to test competing hypotheses that can explain major unresolved mysteries in the evolution of not just the taxa at hand, but also in terrestrial vertebrate radiations in island archipelagoes across the globe. By carefully studying this awesome group of ‘dwarf kingfishers’ we showed that the “paradox of the great speciators” was hardly a paradox at all, and is actually quite expected under a simple model of shifting selection pressure on dispersiveness, through time.